Blog

Stories from my personal journey learning about and delivering Nature-rooted programs across three different countries

Aggression or distress? Behaviour in the outdoors...

Caylin (Forest Schooled)

Empty space, drag to resize

Short on time? Listen to this blog post as a podcast. And subscribe to my podcast channel on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, or Spotify.

I could see him shaking.

His fists were clenched and his jaws clamped so tightly that the muscles were visible in the contour of his cheeks. He reminded me of a kettle over a fire when it's just about to boil over.

The group was sitting in a circle and I happened to be the only staff member facing this boy named Mateo. Despite these signs being physically visible, he was almost silent and difficult to notice unless you had the full view like me.

The group had returned from exploring in the forest and it seemed a younger (and very boisterous) child had not heeded the boy's request for space. I noticed Mateo's annoyance as they returned to our circle after being called back, but it wasn't until he sat down that I watched it turn into what looked like anger.

I knew he needed support with these strong emotions before it escalated. But like trying to hold a burning hot coal, it required tact and strategy.

Calling attention to him at that moment where he would suddenly become the focus of the group did not seem appropriate. I waited until the circle discussion was over and continued to observe him from where I was sitting. The other children dispersed but Mateo remained seated, still fuming.

So, what do you do in these circumstances?

The answer is simple. The implementation may not be...

But before I tell you what I did in this scenario, I want to ask you the question, is the behaviour aggressive? Or distressed? And how might that question itself reframe how you respond?

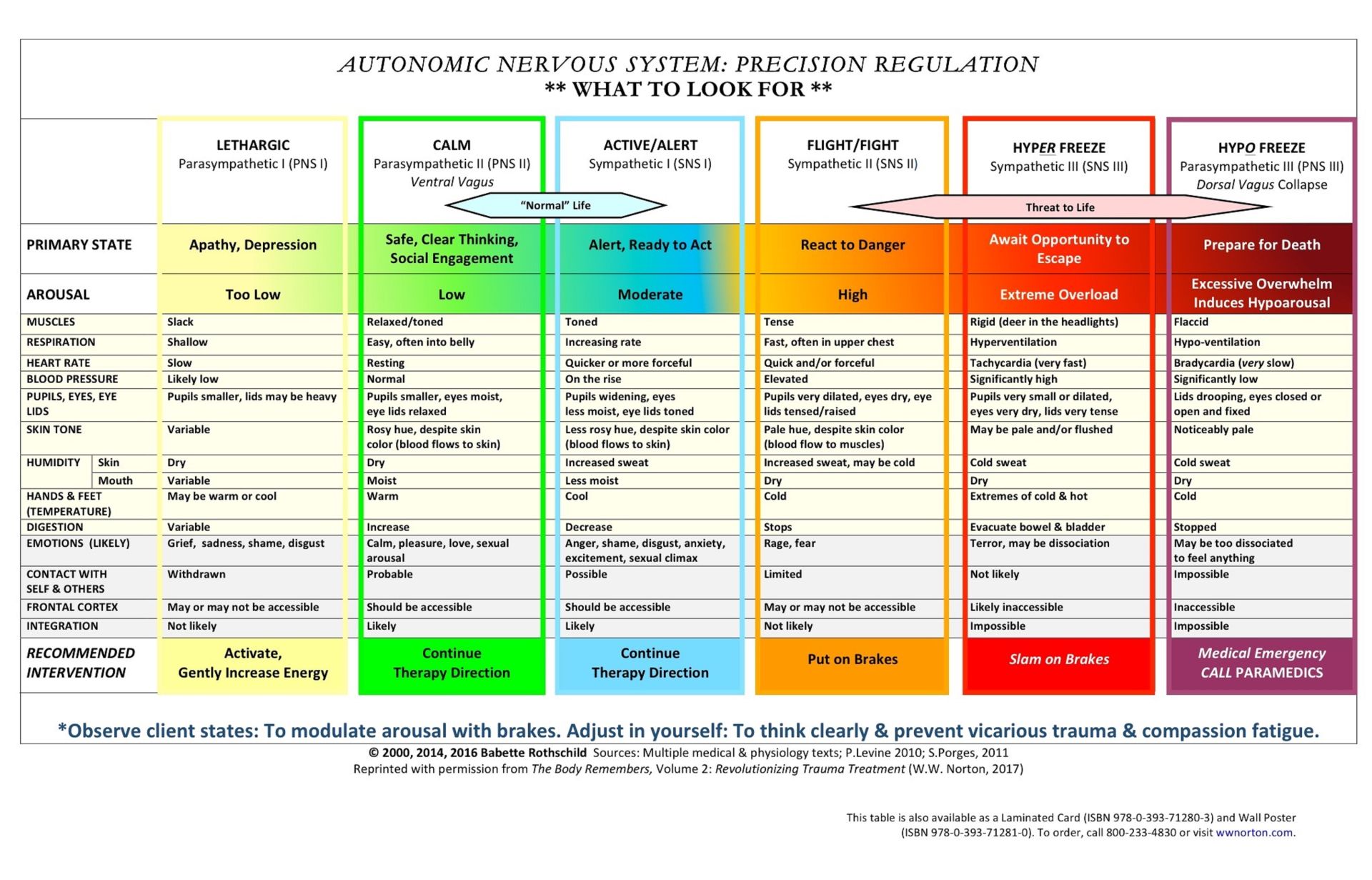

In our recent online course, "Intro to working WITH distressed behaviour in the outdoors," Jon Cree (course co-facilitator and author of The Essential Guide to Forest School & Nature Pedagogy) introduced us to the work of Babette Rothschild, a body-psychotherapist and specialist educator in the treatment of trauma and P.T.S.D. Rothschild brings our attention to the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS).

If you're not familiar with the ANS I appreciate this simple overview from Washington University's Neuroscience for Kids:

"The autonomic nervous system (ANS) regulates the functions of our internal organs (the viscera) such as the heart, stomach and intestines. The ANS is part of the peripheral nervous system and it also controls some of the muscles within the body. We are often unaware of the ANS because it functions involuntary and reflexively... The ANS is most important in two situations:

In emergencies that cause stress and require us to "fight" or take "flight" (run away)

In nonemergencies that allow us to "rest" and "digest."

If we choose to reframe "aggressive behaviour" as "distressed behaviour" then our whole perspective can shift. It's not about managing or controlling the behaviour, it's about responding to a distressed nervous system to help bring the person back to a regulated state.

Rothschild has created a chart that clearly outlines how to identify and support behaviour in these different nervous system states. The image of the chart is posted below and you can watch this YouTube video

of Rothschild explaining its development.

If we look at Rothschild's chart, I think it's possible Mateo was approaching the flight/fight state (or Sympathetic II) in the orange column. The chart describes physical changes such as tense muscles and fast respiration focused in the upper chest. It also tells us what's happening in the person's brain, like the frontal cortex (area responsible for self-management and decision making) which may or may not be accessible. Therefore it is essentially pointless to try to engage him in any rational thought processes at this time.

Now I'll tell you what I did and along the way I invite you to consider what you would do...

Since I could feel my own nervous system responding to the situation with anxiousness I knew I needed support. I also knew Mateo had a stronger relationship with another member of staff named Noah. I was only a substitute and had been with this group just a handful of times while Noah had been with some of them for years. So rather than trying to support Mateo on my own, I went straight over to Noah and confidentially let him know what I was observing.

Mateo had a history of angry outbursts related to frustration and, I suspect, low self-esteem. It seemed he also had some stressful circumstances at home. Noah knew more about this than me so we agreed he would be the main one to respond to Mateo.

He gently approached Mateo and invited him to walk with him to another more secluded part of the forest away from the rest of the group. Noah began to walk away motioning for Mateo to go with him, but Mateo didn't move and continued to clench and breathe rapidly.

I slowly knelt down near him so he could hear me, but with enough space so he wouldn’t feel confronted. I stayed silent for a moment while I felt the supportive ground underneath me. This helps me in those moments to stay calm. I then chose to speak softly to Mateo and acknowledged we'd noticed he looked upset. I said, "Noah wants to help you. He's just over there if you want to go speak with him."

Mateo looked at me, said nothing, but then stood up and walked over to Noah and they went off together.

I did not witness the rest of Noah's interaction with Mateo, but I know that spending even a few moments in a quiet space in a natural environment with a supported and regulated person is very soothing to our nervous systems. A while later, both Noah and Mateo returned in a calm and relaxed state, and it seemed most of the group never even knew what happened.

Now, just because this approach helped in this scenario does not necessarily mean it's the only way, nor the best way for every child! However there are three significant parts to my example I believe are crucial.

- Mateo was supported by someone who he already had a strong and trusting relationship with. We made sure this was prioritized in our response. See "Supporting behaviour through relationships instead of rewards and punishments" for more about this.

- Both adults working with Mateo (me and Noah) maintained awareness of our own nervous systems and were able to stay reasonably regulated.

- We were outdoors in a natural environment. See “Nature and the Nervous System” for more information about why this is significant.

I want to emphasize the second point for a moment.

Earlier when I asked what would you do in these circumstances, I said the answer is simple. That's because one of our greatest tools in working with distressed behaviour is to track our personal response patterns in our OWN autonomic nervous systems.

We must focus on ourselves.

At first glance this may seem odd, as many of us want to learn strategies to support others like children and their families. However, the more we learn about behaviour's connection to our brains and bodies, the clearer it becomes that self-awareness is in itself a strategy for supporting other's behaviour. (Note: If you're not familiar with polyvagal theory, I highly recommend this resource: A Beginner's Guide to Polyvagal Theory).

The reason I then said the implementation may not be simple... is because I wonder how many of us have this level of awareness about ourselves?

I know I did not for most of my life, and am still very much learning. I suspect the reality is that many people operate day to day in a state of functional dysregulation - all of which is highly connected to trauma, especially significant for those in marginalized and oppressed groups!

We talk much more about the role of co-regulation with other humans and the natural world and why this is so important in our course "Intro to working WITH distressed behaviour in the outdoors," but for now I want to share a simple technique Libby Piper (course co-facilitator, neuroscience student, and creator of Honeysuckle Hugs) introduces to course participants that I also use with the children in my programs.

It's a tool to assess our energetic state of being and is called the "self-awareness gauge."

Libby says, "It looks almost like a number line with one being on the left side and ten being on the right. The most important thing to remember is to use this gauge without judgement. There is no need to assign our energetic state of being qualities like "good" or "bad." They are simply a reflection of our environment."

One is associated with qualities like fatigue, dullness, stickiness, heaviness.

Five is associated with contentment, peacefulness, a place where curiosity is readily available to you.

Ten is a little hyper, fast-paced, buzzing.

When you’re in a place where you feel comfortable to do so, check in with yourself and see if you can assess where your energetic state lands. Near one? Near ten? Or are there qualities of both? Whatever you're becoming aware of, notice it, maybe write it down, and then let it go...

We've created an image of a number line, but you are welcome to personalize this. Instead of a scale from one to ten, what best represents your range of nervous system sensations more neutrally than words? E.g. colours? Shapes? What else?

I have been sharing this technique with children at Nature School.

We do it at the beginning of our day and at the end, and discuss any changes we notice and how it may relate to the time of day, weather, and more.

We do it at the beginning of our day and at the end, and discuss any changes we notice and how it may relate to the time of day, weather, and more.

Instead of numbers, I think of the gauge in terms of herbs. Lavender is my favourite plant and brings me peace and contentment so it represents the middle for me. Chamomile is very calming and it helps soothe me when I'm overly stimulated. Mint, on the other hand, is activating for me. It's invigorating and helps me gain energy when I'm feeling sluggish. Here's a drawing I made to represent my gauge.

The children started to think about what representations they'd use in their gauges. One five year old who loves dinosaurs chose "T-rex to Velociraptor." Another chose "sleepy cat to excited puppy." Sometimes we use our imaginations in this exercise, while other times I draw a line in the dirt so they can move their bodies to demonstrate where they are on the gauge should they wish to share.

We do this every session now and not only is it helping us all develop awareness of our nervous systems, it's also a reflective tool that helps me as a leader gain insight into how the children are feeling, and what they need.

It's become a wonderful way to help ground us in our bodies, physical sensations* and what they mean, and to the earth beneath our feet!

The other day one girl shared that her hyper and buzzing state of being felt like "popcorn." How insightful!

If you're looking to deepen your awareness and knowledge of how to work with behaviours that are challenging, I've teamed up with some expert facilitators to offer a course "Intro to working WITH distressed behaviour in the outdoors." You can sign up to be the first to hear about when we offer it again here.

*It's important to note that noticing physical sensations in the body is not always easy nor beneficial for everyone, especially for those who've experienced physical trauma. Connecting with the body can be very intense and triggering for some people so it's important to be trauma-informed when leading others in activities that focus on the body.

References:

Dana, D. (2018). A BEGINNER’S GUIDE TO POLYVAGAL THEORY. https://www.rhythmofregulation.com/_files/ugd/8e115b_f304b2d8bd4144bda80e837fec08e2f4.pdf

Neuroscience For Kids—Autonomic Nervous System. (n.d.). Retrieved May 1, 2022, from https://faculty.washington.edu/chudler/auto.html

Rothschild, B. (n.d.). SOMATIC TRAUMA THERAPY. Retrieved May 1, 2022, from https://www.somatictraumatherapy.com/

More Posts

WANT TO GET FOREST SCHOOLED TOO?

Subscribe to my email letters, something special from me to you so we can learn together. Each one is filled with heart-felt stories from the forest, resources you may find useful, and things that hopefully bring a smile too.

Thank you!

© by FOREST SCHOOLED